A Product Owner by Any Other Name…

By Alan O'Callaghan

There are questions that tend to haunt you throughout your professional life. One of the most asked of me as an Agile coach and trainer is “What is the difference between a Product Owner and a Product Manager?” Good question.

What is a Product Manager?

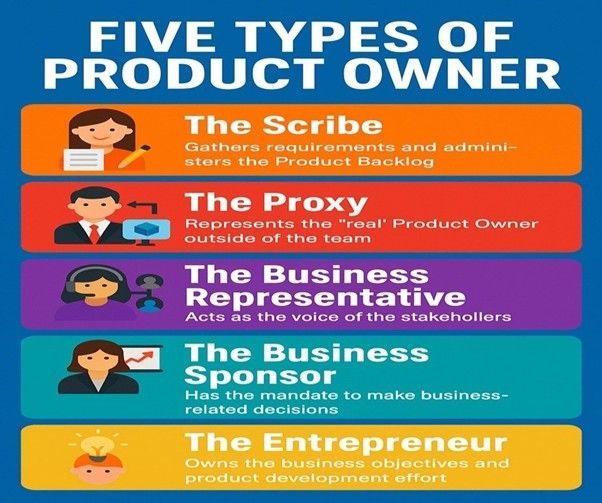

The answer depends first of all on what you think a Product Manager is. For example, in the Silicon Valley Product Group (SVPG)’s Product Operating Model there is a role called ‘Product Manager’. Their model is an abstraction of the work of highly successful product companies such as Microsoft, Netflix and Spotify. SVPG defines a product company as one in which technology, rather than serving the business, is the business. The group’s founder, Marty Cagan insists the competencies of a Product Manager are the most difficult new ones to establish. Why new? Because, despite the title being a traditional one, what is required in the Product Operating Model is a very different job, with very different skills and responsibilities. He characterises the traditional Product Manager as a roadmap administrator who essentially co-ordinates between different internal stakeholders. Solving customer problems, determining a product’s value is the province of those internal stakeholders. Key decisions are taken in committees of the stakeholders, with its meetings facilitated perhaps by the Product Manager, but she is subservient to them while trying to find common ground between them.

“Behind Every Great Product…”

In contrast to the traditional model, Cagan’s Product Operating Model requires a Product Manager to have the responsibility for evaluating opportunities, and then deciding what gets built and delivered to customers. These choices are most often reflected in a Product Backlog. To do this effectively the individual concerned needs the following:

· Deep knowledge of the customer

· Deep knowledge of the data and analytics concerning the customers’ use of the product

· Deep knowledge of the business

· Deep knowledge of the market and industry sector in which the business is competing

Cagan writes “It is my strong belief…that behind every product there is someone – usually someone behind the scenes, working tirelessly – who led the product team to combine technology and design to solve real customer problems in a way that meets the needs of the business” (1). This is the person that he calls the Product Manager. It is someone, he says, who has the competencies and the personality of a CEO, but with the key difference that she is the boss of nobody.

Accountability of a Product Owner

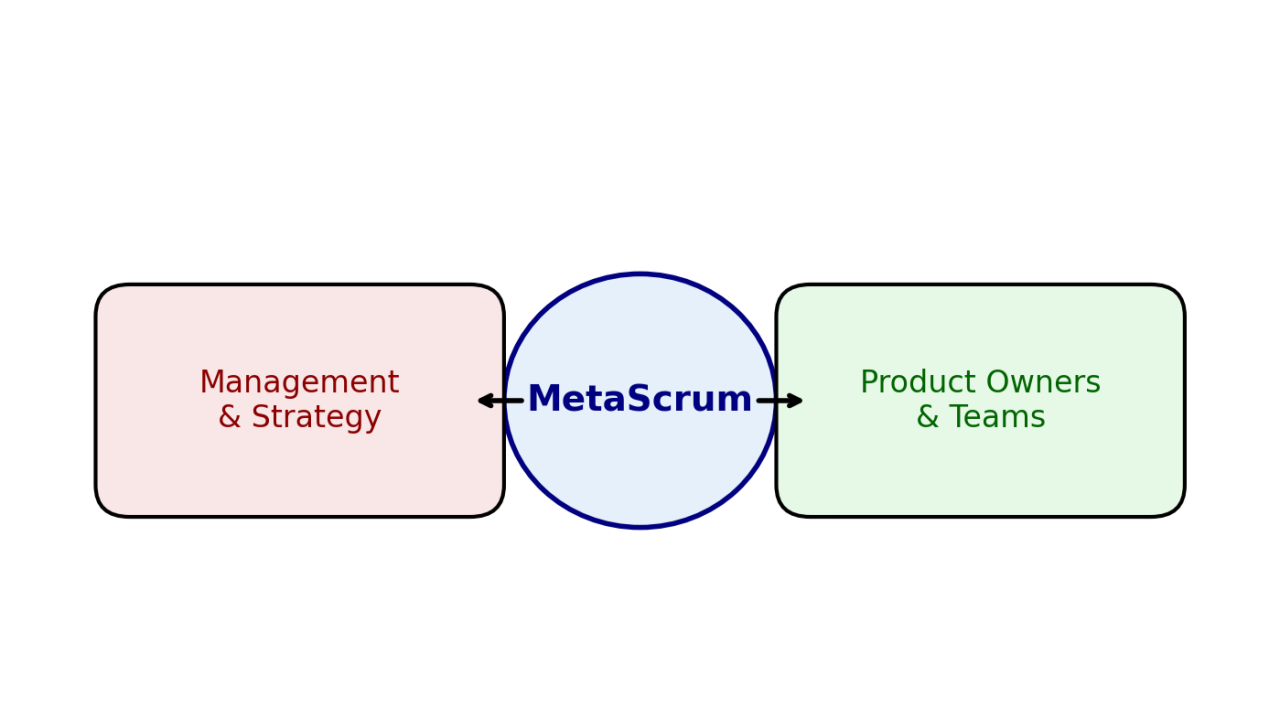

Well, I call her the Product Owner. The concept of the Product Owner originated in the Scrum framework. The framework has always used terms that emphasize that what is required is something very different from traditional practices and mindsets: hence ‘Scrum Master’ and ‘Product Owner’. Product Owner is not necessarily a job title, nor even a role. Crucially it is an accountability within the self-managing Scrum team. Let’s mention here that in the Product Operating Model the Product Manager is similarly embedded in an empowered Product Team.

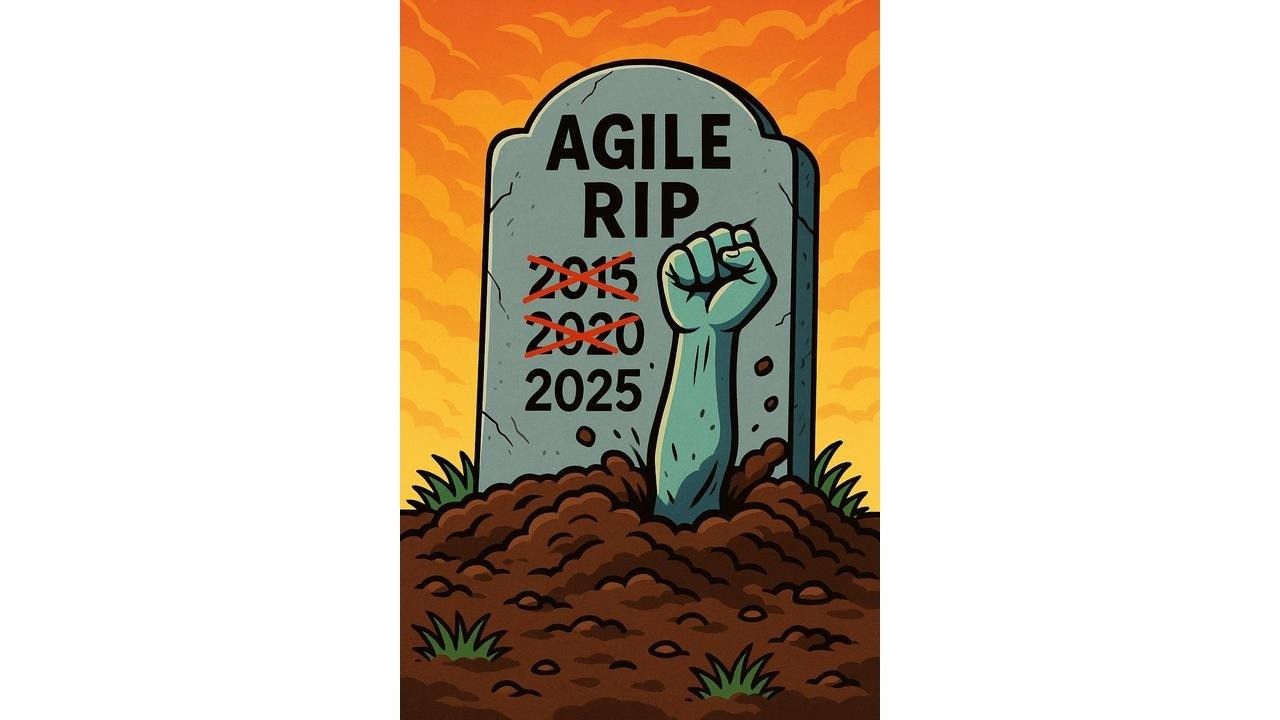

What the Product Owner is specifically accountable for in Scrum is managing the Product Backlog and maximizing the value of the product resulting from the work of the Scrum team. These accountabilities are spelled out explicitly in The Scrum Guide. So why don’t the SVPG call this key role in their model ‘Product Owner’? Because they describe Product Owners as Backlog administrators who escalate every decision and issue to senior management. More than once, Cagan has said that this is the kind of job that is described in a Certified Scrum Product Owner (CSPO) class. When I played a video clip of Cagan saying exactly that, to a very experienced and successful Product Owner that I had originally trained he laughed and said “Well, he clearly never attended your CSPO class”. Nor a class given by Zia Malik, Matt Roadnight, Martine Devos, Nigel Bear or any of the CSTs in Scrum Alliance that I know that deliver the course.

Were it the case that a Product Owner’s accountability was restricted to managing the Product Backlog then the accusation that they are merely Backlog administrators would have some validity. I don’t doubt that there are a great many people labelled ‘Product Owner’ in their organizations who lack the leadership qualities that Scrum demands, and are basically rebadged Business Analysts. But if they are among the estimated 400,000 certificants created globally by either Scrum Alliance or scrum.org then they were not trained to be administrators.

Maximizing Value

The key issue is the Product Owner’s accountability for maximizing the value of the product. She orders the items in the Product Backlog so that the Scrum Team is always working on the most important thing to deliver that value. It is the self-managing Scrum Team that is charged with solving the hard problems the customers face, not the internal stakeholders. For them to be able to do that and stay in alignment with the wider organization their Product Owner has to have a keen understanding of the business’ strategy, develop a strong Product Vision and communicate the various market strategies the product will need over its lifetime. Each of these strategies will need an outcome-oriented roadmap providing the context for the Product Owner’s decisions on the ordering of the Product Backlog.

In reality there is a lot of overlap between the SVPG’s concept of a Product Manager and Scrum’s Product Owner. They are both very different from the traditional Product Manager. They both make use of a Product Backlog. They are both embedded in an autonomous product team. They are both accountable for delivering maximum value to the customer in a way that benefits the organisation.

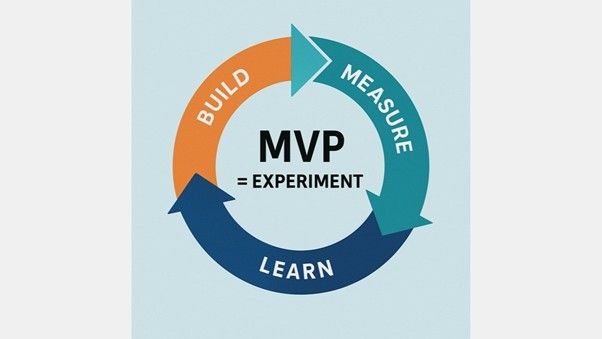

The Product Operating Model is simultaneously broader and narrower than the Scrum framework. It is broader than Scrum in the sense that it addresses issues in the wider business directly. The Scrum framework leaves it up to individual organisations to work out how Scrum teams fit their particular context. The Product Operating Model is narrower than Scrum in that it applies only to technology companies while Scrum can also be applied to marketing, education and even restaurants. I love the Product Operating Model’s insistence on product teams rather than project teams (Cagan calls these feature teams). Scrum can be used on projects but customers buy products, not projects, and leveraging the investment in self-managing Scrum teams is best done by keeping them together, working on one product at a time rather than splitting them up at the end of a project. I consider continuous Product Discovery and building products through rapid experimentation – key themes in the Product Operating Model – to be essential in Scrum too.

Upskilling Product Owners

The underlying reality is that whatever you want to call them – Product Managers or Product Owners - there is a desperate shortage of people with the skill and the authority to lead product teams that can solve the hard problems that customers face. It is not about changing job titles. It is about making a serious investment in upskilling those people and equipping them with whatever they need to be effective.

(1) Marty Cagan. Inspired- How to Create Tech Products Customers Love 2nd edition p5 .2018 John Wiley.

First published on LinkedIn August 4th 2025