Meaning is in the Eye of the Beholder - MVP

by Alan O'Callaghan

The worlds of business and product development are awash with acronyms. While they can be useful shorthand for complicated concepts, they have a tendency to degrade over time and the understanding of what they mean gets fuzzy. Meaning, like beauty, is then in the eye of the beholder. ‘MVP’ is one of those acronyms which seems to have attracted both beautiful and ugly meanings to itself.

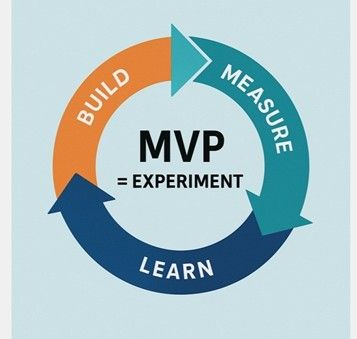

MVP stands for Minimal Viable Product and was popularised by Eric Ries in his book The Lean Startup. A Build-Measure-Learn feedback loop is at the heart of his Lean Startup model. He explains “The MVP is that version of the product that enables a full turn of the Build-Measure-Loop with a minimum amount of effort and the least amount of development time.” (1) The very fact that it is a minimum product tells us that not all of its planned features will be included in the MVP. Even essential features might be left out. Often people focus on the ‘Build’ part of the loop and use it as an excuse to release a product that has too little functionality to be considered either valuable by customers or viable by the business. Some engineers even use ‘MVP’ as an argument for cutting corners on quality assurance:” It’s only an MVP. We can build in the quality later in the full product”. They appear to be practising development agility because they are delivering incrementally – and we definitely favour small increments in Agile product development – but where’s the value if no-one wants to use it, and who wants to use a shoddy product?

Product-Market Fit

MVPs are not about reducing the product’s development effort. In fact the use of an MVP increases the effort required because its impact has to be measured. An MVP is essentially an experiment. It is testing the emerging product to see if it is likely to deliver the value proposition embedded in the Product Vision.

MVPs are usually targeted at product-market fit. Product-market fit means having a product that can satisfy a market. By definition, that means building a product that creates significant customer value. In turn, that requires meeting real customer needs in a better way than any competitor products.

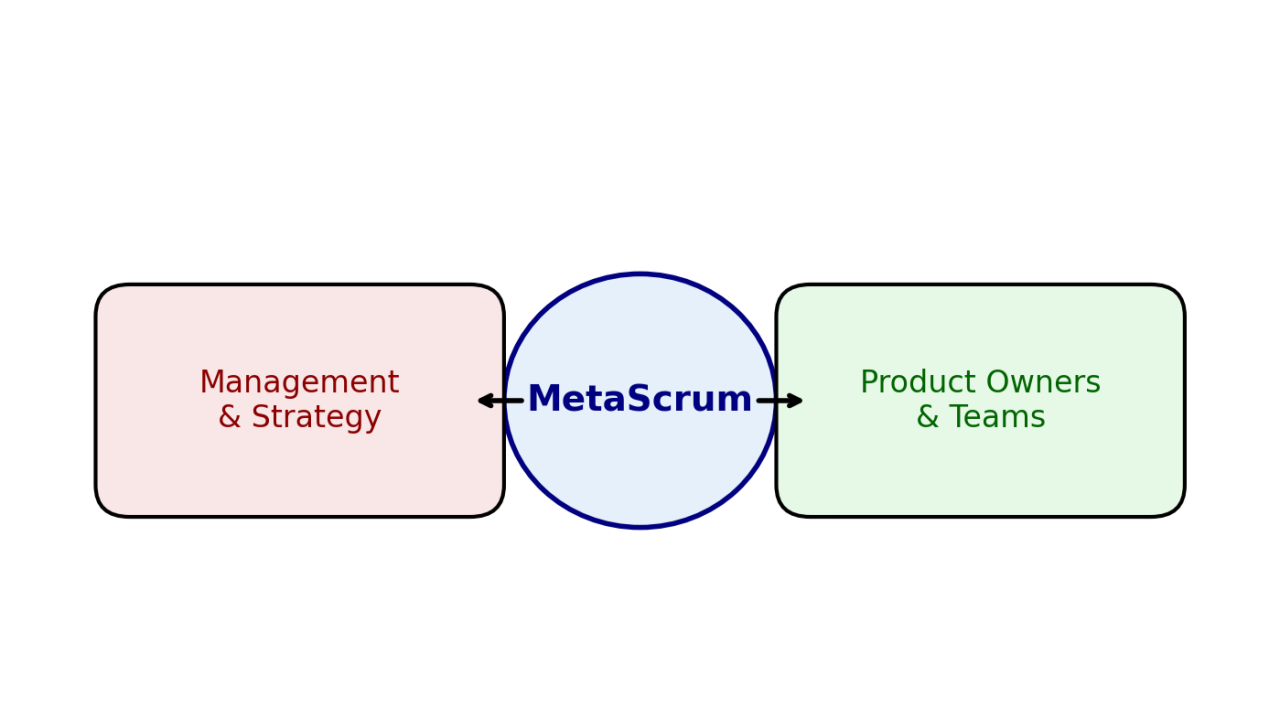

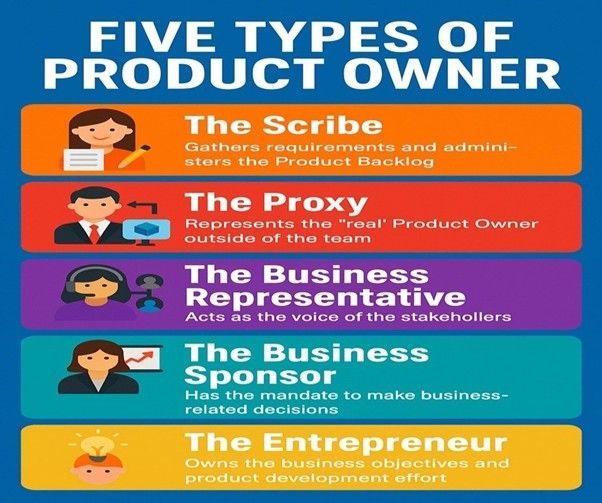

The Product Owner has an essential role to play here. She has first to identify who the real customers are, and secondly decide which of their needs are underserved, and in what way. This is the thinking that should underpin the selection of the feature set for the MVP. Those features which address the customers’ top pains or offers them the most benefit should be prioritized. Brainstorming a list of features is easy. Deciding which four or five are the most important is really hard. And it is really critical. Of course, at first these are just hypotheses. It is the release of the MVP to the market, and the feedback from customers that will tell us whether it’s moving in the right direction to achieve the Product Vision. Increments that are demonstrated internally and are not placed in front of real customers should never be called MVPs. Quantitative measurements can tell us how many customers have bought the product, how the end-users interact with it and such like. Qualitative feedback is needed to tell us why they use it in a particular way. MVPs give us data that can lead to a go/no go decision about whether or not to build a solution and grow it in the market.

Pivot

The nature of a hypothesis is that it could be proved right or wrong. If our assumptions are wrong, we will need to pivot. The worth of an MVP is that it can tell us sooner that is time to change direction, saving money and effort in the process. Startups that use MVPs in this way are capital-efficient and are more likely to survive but, clearly, more established organizations can also use an MVP to validate assumptions about new products or innovative features.

MVP tests

Given what I’ve just said, I suppose that there can only be one MVP in a product’s lifecycle. I’ve witnessed many a lively debate about whether there can be one or many. And I’ve usually stayed outside of them unless one of the ugly meanings I mentioned before is raised. For sure, the Product Owner will be prioritizing features and work packages throughout the product’s development, but deciding which few are the key ones to deliver on the Product Vision seems to distinguish the MVP from increments that are delivered later.

Having said that, similar thinking can be used at various points during development to test key assumptions and get new learning. Dan Olsen calls these ‘MVP tests’ (2) and I like this idea. Faced with an unknown or a particular risk, the Product Owner will work with the engineers in the Agile Product Team to identify which features are needed, in a prototype perhaps, to uncover a new learning point or address the risk.

Four Product Risks

There are four kinds of risk that the team, under the guidance of the Product Owner needs to bear in mind all the while:

Value. This is the risk that nobody will want to buy or use the product- that it is essentially not fit-for-purpose. While this is the risk that MVPs usually address most, it will still need to be revisited even if the MVP validates initial assumptions.

Usability. If the customers can’t work out how to use the product, they will eventually walk away from it and it will have no value. Prototypes can be built rapidly and cheaply to test which kind of interactions the customers prefer before the product team commits to any particular solution.

Feasibility. Can the engineers build the solution with the resources available? This includes technology, skillsets, budget and time. Ruthless prioritisation by the Product Owner is key here too. If the product team is always working on the most important items then it is likely they will deliver customer value even if budget and time constraints prevent them from delivering full scope. Spikes might be needed to address technology or skillset-based risks.

Viability. A given solution might be very attractive to customers, but can the organization support it in the marketplace? The potential issues range from whether the business can make a sufficient profit, to whether its existing business model needs adaptation.

An initial MVP might begin to answer some of these questions, but the reality is that the Product Owner will repeatedly have to ask, “Which subset of features do we need in the next increment to address this risk?”. Continuous product discovery and rapid experimentation will be needed throughout the product lifecycle to maximize customer value in the face of change, and in a way that benefits the business.

Questions for You

· What is the understanding that your organization has of ‘MVP’?

· How do your teams address risk?

· How do you measure a release’s impact?

(1) Eric Ries. The Lean Startup: How Constant Innovation Creates Radically Successful Businesses. p.77. Portfolio Penguin. 2011

(2) Dan Olsen. The Lean Product Playbook. How to Innovate with Minimal Viable Products and Rapid Customer Feedback. Wiley. 2015

First published on LinkedIn September 22nd 2025