The North Star isn't a Destination - but it lights the way

by Alan O'Callaghan

Although not explicitly mentioned in The Scrum Guide, Product Vision is an enormously powerful tool in the hands of a Product Owner. It provides a bridge between a product’s strategy and the business strategy of the wider organization. It is crucial in enabling the autonomy of the Scrum team by ensuring its business alignment, and its use tends to highlight problems in the way an organization develops its products and services. It opens up opportunities for the business to take actions that improve its ability to satisfy its customers. The need to upskill its Product Owners is often one of them. The Product Vision is a kind of North Star. It lights the way and, in doing so, often reveals things lurking – previously unseen – in the shadows.

Business Strategy

Let’s sort out some terminology first. In product management the same words can mean different things to different people. So, what do I mean by ‘business strategy’. Roger L. Martin (1) claims that an effective business strategy answers the following questions:

What is our winning aspiration? What is the fundamental purpose of the business – why do we exist, beyond just making money?

Where will we play? Which markets, geographies, customer segments and distribution channels will we focus on?

How will we win? What is our unique approach to create superior value for customers and deliver a sustainable advantage over competitors – and which ones will we deliberately not pursue?

What capabilities and systems must be in place? What critical competencies, resources or ways of working must we build or acquire to deliver our winning way?

What management systems are required? What structures, measures, incentives, and governance are needed to support the strategy and ensure continuous adaptation?

Answering those questions takes an organization beyond the vague aspirations embodied in, say, a mission statement to make clear, hard choices. Mission statements and business strategy are - quite properly - devised, owned and communicated by the organization’s senior management. But the sad fact is that most companies avoid the kind of brutal prioritization that Martin is implying.

Instead of stating clearly which of their customers’ pains they should address with their products, internal stakeholders come up with business cases for individual projects, use them to compete for a share of funding (often on an annual basis) and, if they are successful, hand their ‘solutions’ over to project teams for execution. This approach is commonly called the peanut butter strategy (2). Resources are spread too thinly across the development organization and over too many products and services. The peanut butter strategy is in fact the absence of business strategy. Instead of the senior management deciding which areas of customer need they should prioritize, the financial arm is ranking proposed solutions identified by various department managers. Decisions are made on the promised Return on Investment (ROI) contained in their separate business cases.

Product Vision

A Product Vision is a stable, aspirational goal that describes the kind of product that is needed to meet some aspect of a business strategy. My favourite example of a Product Vision was the one for the iPod. Apple released the iPod in November 2001 after 8 ½ months of rapid experimentation and development. The vision Steve Jobs gave to his senior engineers was for a device that could fit in his pocket, hold at least 1000 tunes and would be easy enough for his mother to use.

In 1997 Apple was 90 days from being bankrupt. Dell’s CEO commented at the time that if he were in charge he’d “shut it down and give the money back to the shareholders”. Then Steve Jobs returned. He killed 70% of the products Apple was shipping in his first year. He slimmed the company’s portfolio down to just two desktops and two laptops for consumers and computer professionals. He diverted a large part of the R&D department’s budget into marketing and launched the “Think Different” campaign that proclaimed that Apple is for passionate people who want to make the world better.” The campaign advertised the core values of Apple rather than any individual products, but the vision he had for the iPod fitted right into the new strategy. Apple wasn’t just saved from bankruptcy it was turned into the richest technology company in the world by Jobs’ strategy.

Product Visions usually get elaborated in an envisioning workshop, facilitated by the Product Owner, that involves a diverse group of stakeholders as well as some engineers. Its job is to boil down potential features to the most important ones. Creating a list of potential features is easy. Boiling them down to the three or four critical ones for a product’s success is much harder. In the absence of a business strategy, it gets extremely difficult. Different stakeholders champion their own pet features in competition with each other. The Product Vision says “This is the kind of product we need to do…” To do what? In the absence of a business strategy the question is almost unanswerable. Peanut butter, anybody?

Towards a Product Model

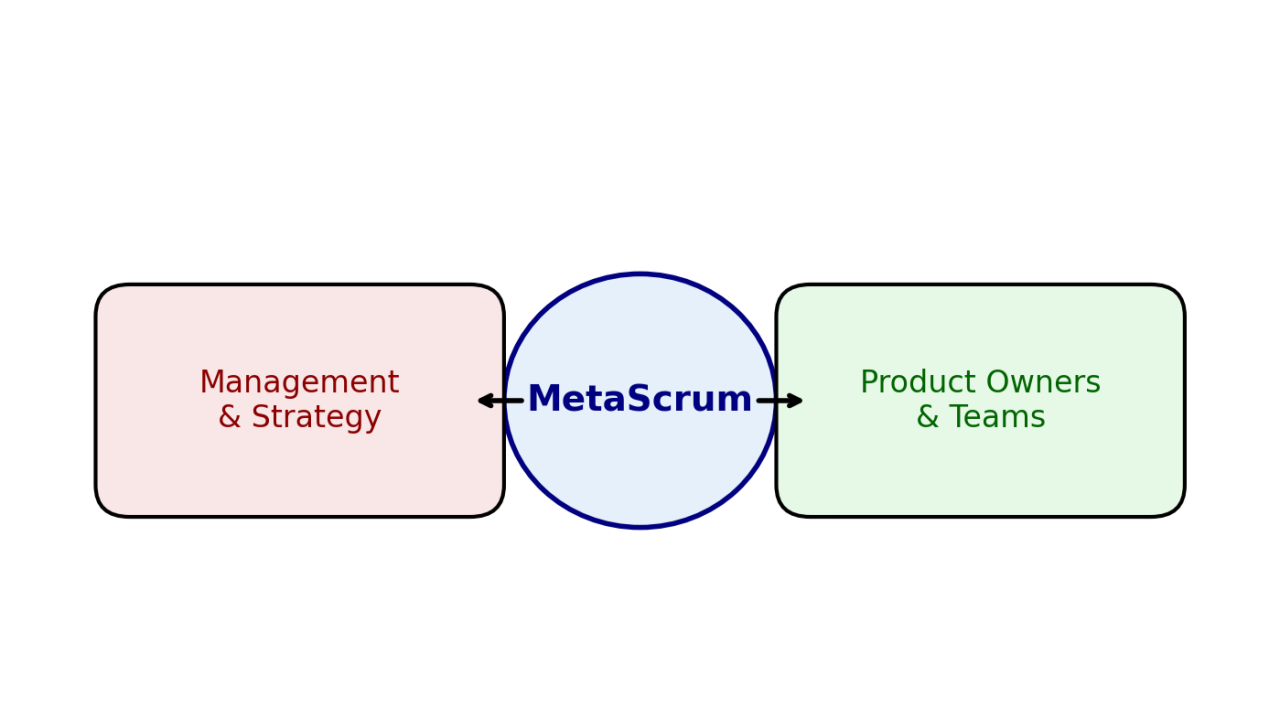

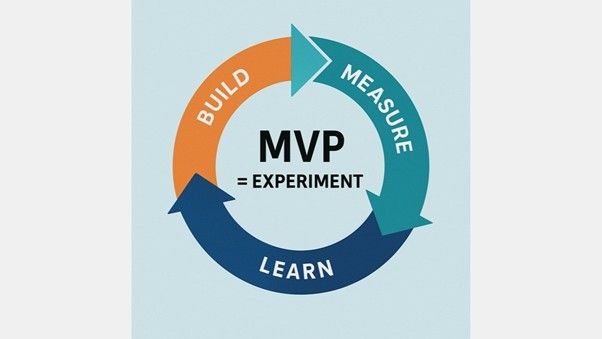

Fractious envisioning workshops are often symptoms of a bigger, underlying problem: the organization as a whole has an insufficient focus on its customers’ priorities. The senior management is the body to redress that. But the issue is exacerbated when the organization’s focus is on projects rather than products. Customers buy products and services, not projects. The most successful businesses place problem-solving in the hands of product teams, not internal stakeholders. A team, led by the Product Owner embedded in it, is given a customers’ problem to solve by management. The product team is empowered to figure out the best solution. In these circumstances, the Product Vision has a clear link to the business strategy (which is based on the superset of customer problems the company has focused on), while at the same time providing a value compass to the development effort itself. Individual feature requests can be compared to the Product Vision and judged as to whether they contribute to it or take the product off at a tangent. In the latter case, the Product Owner should reject the request out of hand. Product strategies to implement the Product Vision; to gain market-fit, or to or maintain market share, and the roadmaps associated with these strategies provide the context for the ordering of the Product Backlog, helping the Product Owner to maximize the value resulting from the work of the Scrum Team.

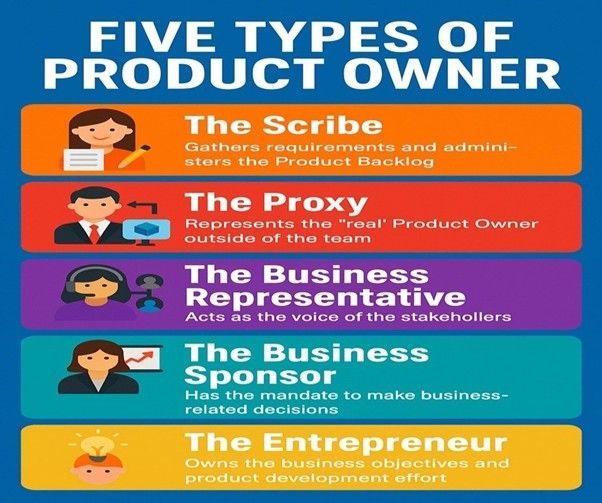

Empowering Product Owners

All this implies a change in the position of Product Owners relative to the rest of the organization. In project-centric companies a Product Owner is, at best, a roadmap manager, arbitrating amongst the different stakeholders who each want their project’s features to rank highest in the Product Backlog. A genuine Product Owner is described by the name on the tin. She owns the product. To do that she will need to know the business strategy; have a deep understanding of the customers’ needs and how her product might serve them; drive product strategy and elaborate outcome-driven roadmaps. This is not just an upping of her authority; it demands that her skillset be raised to new levels. The choice for organizations is to invest in their Product Owners or eat peanut butter for the foreseeable future.

(1) A.G. Lafley and Roger L. Martin. Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works. Harvard Business Review Press. 2013

(2) See, for example, Marty Cagan with Lea Hickman, Christian Ididdi, Chris Jones and Jon Moore. Transformed: Moving to the Product Operating Model. Wiley. 2024

First published on LinkedIn October 6th 2025