By A O'CALLAGHAN

•

May 24, 2022

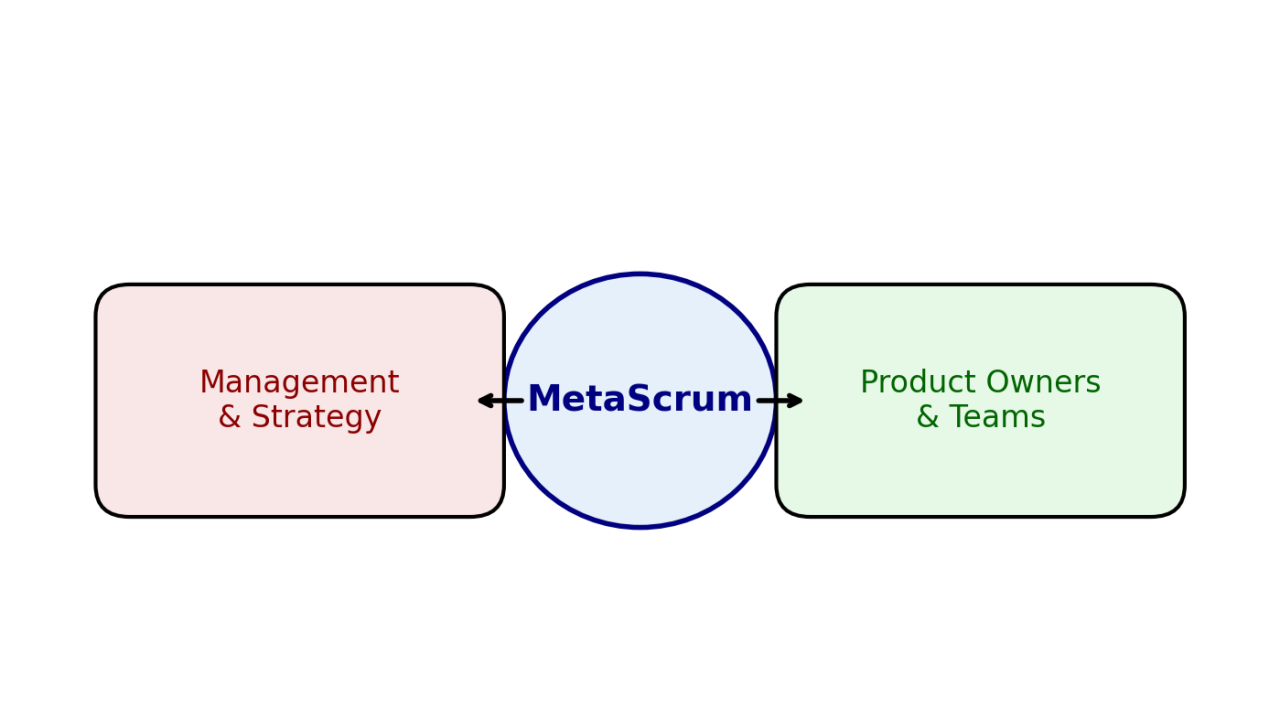

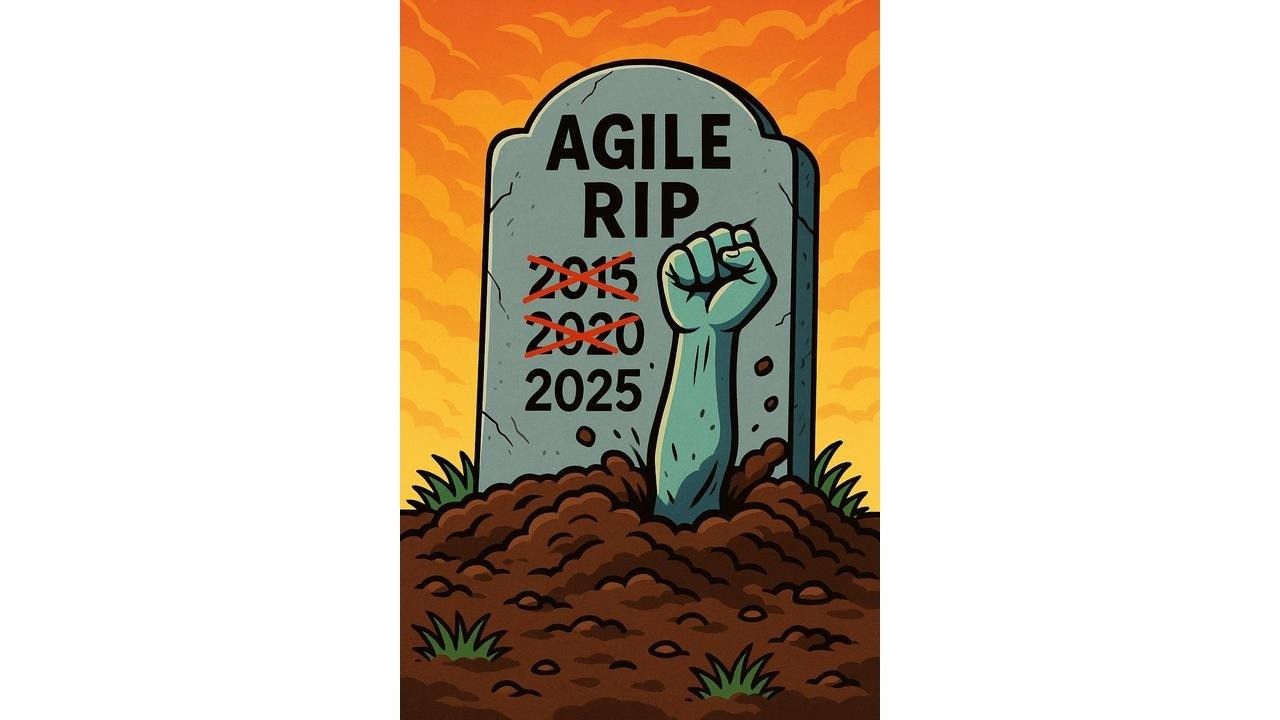

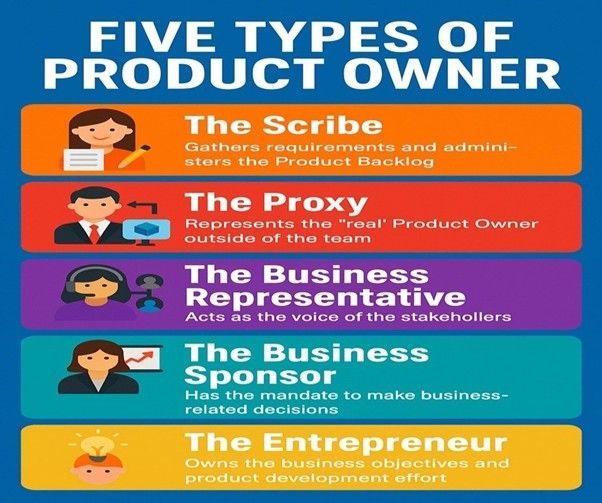

In 1897 Mark Twain famously complained that reports of his death were exaggerated. A hundred and twenty five years later the reports of the death of Agile similarly abound, and are just as far off the mark. In fact, according to the Business Agility Institute, Business agility – defined by the BAI as “…a set of organizational capabilities, behaviors, and ways of working that affords your business the freedom, flexibility, and resilience to achieve its purpose. No matter what the future brings.” – has increased globally in a very significant way since the start of the pandemic. Other respected authorities, McKinsey, for example, have noted a rush towards Agile ways of working as a consequence of organizations finding flaws and dysfunctions in their existing structures, cultures and processes that hinder their ability to respond to unanticipated change. One wellspring of the rumours of the death of Agile has actually been from well-known Agilists such as Dave Thomas who were actually pointing out that big consultancies have jumped on the Agile bandwagon and corrupted its meaning and intent. Way too many organizations have swallowed the snake oil that suggests Agility is about adopting a few practices in the product development area to become “faster, better, cheaper” while changing nothing else. Agile has always been about responsiveness to change while delivering products that delight customers: “faster, better, cheaper” are second order effects of lowering the cost of change. These are not obituaries, but passionate warnings about the need to defend the values and principles of Agile. A Post-Agile World? A different, but insidious and dangerous perspective comes from those who contrast Business Agility with Agile product development. To the extent that the term “Business Agility” focuses on the need for organizational-wide cultural and structural change, it reflects a welcome shift in an understanding of the challenges businesses face in every sector of the world economy. On the other hand, these are not new problems. The pandemic, supply chain disruption, the ‘Great Resignation’ and even the war in Ukraine have only exacerbated and revealed more clearly the need equip organizations to respond to change and to innovate more quickly. Changing the world of work has always been at the heart of genuine Agile thinking and practice. Yet we are welcomed to the ‘Post-Agile World’ by the authors of one acclaimed book. An Agile Straw Man The book concerned, by Fin Goulding and Haydn Shaughnessy is called Flow . First off, it’s a good book. I recommend it. It is full of interesting ideas to promote cultural change throughout a business. I love their concept of extreme visualization, of work as a learning model, of the need to co-create processes and so on. I see these as valuable additions to our understanding of Agile. But they do not. At one point in the book, they post a table that compares Flow with Lean Startup and with Agile. Agile is summarized in eight bullet points. But their ‘Agile’ is a straw man – easy to knock over because it’s not the real deal. Let’s look at those eight bullet points: “A structure for software programming”. While it is true that Agile took off in software development, it didn’t start there, and it won’t finish there. Most commentators trace Agile thought and practice back to the Shewhart cycle first promoted in 1929. Today, Saab build fighter aircraft, Tesla make autonomous cars, GKS develop pharmaceuticals and the EduScrum movement is transforming education using Agile approaches. “An a priori project-planning method”. I’m not sure where that one came from. One of the four values of the Agile Manifesto is about valuing “responding to change over following a plan.” Agile planning is data-driven. We plan on what we know rather than speculate. But in a complex world we don’t have all the information up front and some of that will change in any case. Scrum, for example has a planning event at the beginning of every iteration precisely because a priori planning doesn’t work. “Risk reduction”. Quite true. But as the authors contrast this with ‘Management of uncertainty’ in their own framework I think they have misrepresented ‘risk reduction’ in Agile as meaning ‘risk avoidance’. In reality, risk is identified and promoted in importance so that it can be dealt with early in Agile development. “Fixed process”. Just a second while I pick myself up from the floor. I’ve spent 25 years explaining to those I have coached or trained in Agile that ‘the process’ is merely the sum total of all the decisions a self-organizing team makes. As such it is adaptive and will be different for each and every team. Predefined processes are a death march in the face of uncertainty and risk. They are anathema to Agile. “Emphasis on avoiding big failures”. Again, I see here an attempt to draw Agile as a conservative risk-aversive approach compared to Flow. Once again, this is a nonsense. Agilists have always advocated “fail fast; embed the learning” as the only way to succeed in a volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous world. ‘Big failures’ are avoided by the emergent behaviour of running safe-to-fail experiments that either validate assumptions or prove them wrong. Agile teams are empowered to take whatever actions the results of such experiments suggest to them. “More supervisory roles”. What are they then? A Scrum Master for example is a servant leader – the very opposite of a supervisory role. A Product Owner has some independent authority but is a peer member of a Scrum team. There is no rank amongst a Scrum team’s developers. As the eleventh Principle Behind the Agile Manifesto says, “The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams” (emphasis added). Self-organization is defined as order which arises through frequent, local interactions rather than being directed externally. You need a peculiar form of mental gymnastics – standing on your head and turning your insides out maybe - to translate that into the idea that Agile requires more supervisory roles “Fulfills the plan”. See the discussion on ‘a priori planning’ above. Finally: “Execution method”. No! To be truly self-organizing, Agile teams have to take ownership of business goals and objectives. The very reason for having a Product Owner in a Scrum team, for example, is so that her business domain knowledge and experience is available to the team as a whole. A Scrum team’s purpose is to deliver business value. That makes it a genuine business unit, not just an execution/implementation unit. How the team achieves its goals and objectives is entirely up to the team itself. Agile Teams vs Business Agility In their blatant mischaracterization of Agile, Goulding and Shaughnessy have taken the caricature of Agile dreamed up by the “faster, better, cheaper” school of thought and put it on steroids. I suppose when you launch any new product you’ll feel the need to differentiate it from ‘competitors’, but in this case the authors of Flow are in danger of undermining the drive towards Business Agility. Many organizations need to heed the words of Nancy Sinatra: ”You keep saming when you oughta be changing”(These Boots Are Made for Walking). The question is what to change? And more specifically, what to change next? Some people like to think of the recent history of Agile as consisting of three waves: first, team Agile (single team product development); second, scaled Agile (multi-team product development) and third, Business Agility. Karim Harbott in his book, The 6 Enablers of Business Agility, describes it that way. That’s fine and good, provided you don’t think that in this so-called third wave the need to invest in Agile teams is somehow in the past. Karim doesn’t think that by the way. In general, it is clear that organizational and cultural change require leadership. But successful transformations cannot be purely top down, and often do not start that way. My friend Jim Coplien often says of empowerment that power is never given, it is always taken. Most Agile transformation drives to date have been bottom-up. Development teams sit in the heart of the value stream of the organization. The products or services they create are what deliver value to the customer. No-one is in a better position to see how existing hierarchies, processes and compliance demands get in the way. No-one is in a better position to understand which impediments and dysfunctions are the most important to remove next. It is not as if, in the so-called ‘first wave’, the vision of empowered self-organizing teams was universally achieved (even in many companies who thought they had adopted Agile). If anything, the influence of frameworks like Safe and DAD in the so-called ‘second wave’ took us all a step backwards. Scrum Masters and Agile coaches will continue to have to fight to increase the space within which self-organizing teams can operate. The measurement of success with Business Agility can only be the value delivered to customers. Business Agility cannot be achieved without continuous investment in self-organizing Agile development teams. Let no-one tell you anything different.