Gathering the Evidence: Continuous Product Discovery

By Alan O'Callaghan

I love who-dunnits. If I’m resting at home in the evening watching TV, unless there’s a compelling football match to watch, I’ll probably watch crime fiction: anything from Midsomer Murders (1) to Sherlock (2). If I’m reading a novel, or listening to one on my Audible account, then the odds are it will be a murder mystery. In some stories the murderer is known at the beginning (think Columbo (3)) and the fun lies in the chase. But my favourite kinds are the ones where clues appear incrementally, there are red herrings and distractions all over the place as the evidence accumulates, and the race is on for the viewer/reader/listener to solve the murder before the fictional detective does.

Agile product development has some similarities with whodunnits. At the beginning there is not enough information to come up with a solution we can be confident in. Significant effort has to be put in to gathering evidence. Some actions will need to be taken before all the necessary information is to hand. The solution emerges over time, based on the evidence. Agile product development is driven by continuous product discovery.

Simpler Days

Twentieth century mass production was simpler. There was an upfront period of product exploration in which a potential solution was designed. Once finished, this phase was followed by a rather longer period of product exploitation in which the aim was to maximize output and, of course, sales. The difference in twenty first century production, where the rate of change keeps rising exponentially, is that the ‘exploration’ phase extends into the ‘exploitation’ phase. Product discovery continues even after product delivery starts. Potentially, it lasts until the product is sunsetted.

Managing Risks

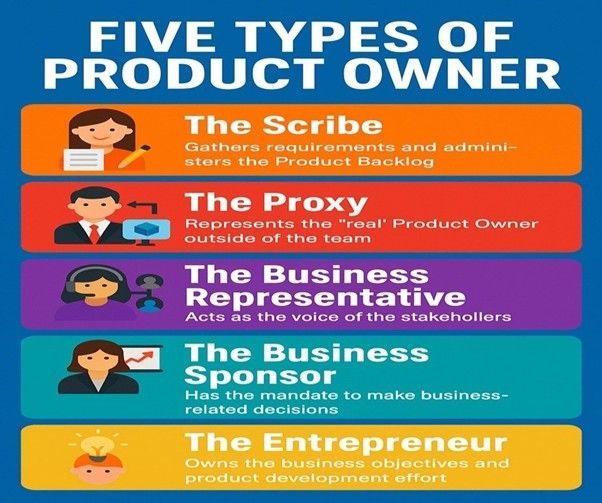

Managing a Product Backlog in the face of unrelenting change involves the management of a number of risks. The most important of these is the value risk: the risk that the organization’s customers won’t buy the product or service. Either it doesn’t sufficiently address their pains, or it doesn’t offer enough significant gains to engage their interest. The continuous delivery of valuable increments, and the feedback from the customers they enable, is the most powerful tool available for managing that risk. Provided, of course, that the feedback is acted upon. In between releases, Sprint Reviews provide a forum for stakeholders and customers to collaborate with the Scrum Team about the increment they just developed. The underlying idea is that many, perhaps most, of the assumptions that we have at the beginning of the development cycle may turn out to be wrong. Incremental delivery, coupled with iterative development, provides a product team with the evidence that either validates or invalidates those assumptions.

Another risk is the usability risk. Customers might like the product’s concept and appreciate its potential for making their lives better, but if the product becomes too complicated or difficult to use they are likely to walk away from it sooner or later. Usability experiments are similarly likely to last through most of the product’s life cycle and, as with the value risk, the best evidence is the feedback from incremental product releases.

The other two big risks are feasibility and viability. Can the organization actually build the product with the resources (materials, technology, skillsets, financial etc.) available to it? And, even if the product can be built, can the organization support it in the market? For example, does the organization’s existing business model support it, or if that model needs changing, is that possible to the degree necessary?

The continuous management of these risks is the very essence of product discovery, but the feasibility risk can be raised if continuous delivery is the only way in which they are managed. Iterative development means rework, and it consumes the resource that is typically the most expensive: engineering. If engineering work gets continually discarded the cost of development may rise to the point where it outweighs the benefits. A good Product Owner will always be open to necessary reworking of the product but will want to keep it to a minimum by gathering as much evidence as possible before her team starts sprinting. The feasibility and viability risks in particular should be largely mitigated before development starts.

Discovery Techniques

The goal in product discovery should be to validate our ideas in the fastest, cheapest way possible. Different discovery techniques are available for different kinds of products, but prototyping is an approach that can be applied in most contexts. The fundamental purpose of any kind of prototype is to learn something at a much lower cost in terms of time and effort than building out a product – even an MVP. A good prototype is a powerful force for collaboration in the product team, helping its members to think more deeply about the risk(s) it is addressing.

The feasibility risk can be typically mitigated through one or more spikes – quick and dirty throwaways developed in timeboxes of no more than a day or two by a pair of Developers. Just enough of the product is created to mitigate the risk – a small percentage of the effort that might be required of an MVP – which might be a performance issue, a scalability concern, or the use of a technology or a third-party component the team has not used before.

The viability risk can be addressed through the use of a Business Model Canvas. Developed by Strategyzer.com the Business Model Canvas can be thought of as a giant canvas divided into nine panels. The central panel is for the Value Propositions. To its right are three panels to do with customers: Customer Segments, Customer Relationships and Channels. To the left are another three panels: Key Activities, Key Resources and Key Partners. Two panels below the other seven deal with Cost Structure and Revenue Streams. In a workshop stakeholders populate these panels with stickies and then collaborate to refine the visualisation of their business model. Easily accessible, the model easily reveals whether a new value proposition sits neatly within the existing business model or challenges it.

Mitigating the value risk should always be done in front of real customers. But a Product Owner doesn’t have to wait for the first release or even the first Sprint Review to begin that process. GV – formerly Google Ventures – uses what it calls Design Sprints to address key value risks before it decides to invest in companies. A Design Sprint – not to be confused with Scrum’s term for a development iteration – lasts five days in which a throwaway prototype is built and shown to a small group of five or more real customers for feedback. Famously they built a fake version of a robot for Savioke to test assumptions about how hotel guests and staff would react to an automaton that delivered room service in hotels. Only after the prototype passed this test did Savioke go into production of the real thing.

Prototypes that address the usability risk are simulations that can range in their fidelity from low (interactive wireframes, for example, that address just one dimension of the product’s usability) to high (close-to-real interfaces but which use low-fi data rather than live data). Typically, low-fi prototypes are used to identify the workflow required before development starts while hi-fi prototypes are used to build usable increments before an actual release which uses live data.

Rapid Experimentation

Different techniques are available for mitigating the various risks, but the key is to remember that whether using a prototype, a simulation or releasing an increment, the team is always performing experiments. The Product Owner uses rapid experimentation throughout the life of the product to discover the features that will maximize the value to the customer while at the same time benefitting the organization. Sister Boniface (4) is not a bad role model for a Product Owner to follow.

(1) Misomer Murders. ITV series. 1996-present day

(2) Sherlock. BBC series. 2010-11

(3) Columbo.NBC series.1971-78

(4) The Sister Boniface Mysteries. BBC studios and BritBox series. 2022-2024

First published on LinkedIn October 16th 2025